We have written many times about the industrial woes of the American economy, the attempts at reindustrialization aimed at sovereignty and, forgive the term, securitization of American industry. This path is long and difficult, if not entirely passable, given the enormous damage inflicted on the U.S. industrial base during the years of globalization. One of the most devastating consequences has been the decline of America’s once-advanced pharmaceutical industry, which has become dangerously dependent on imports.

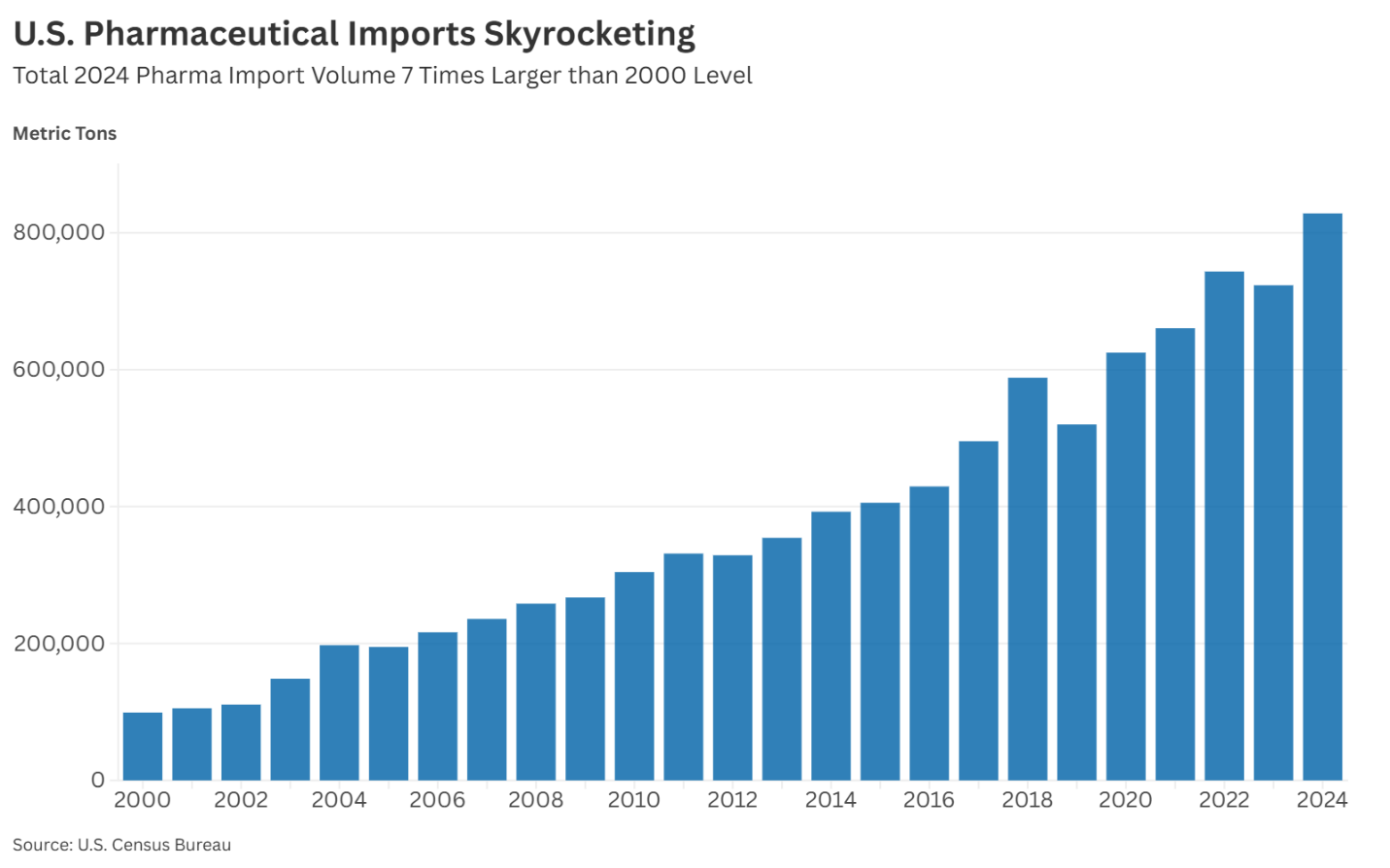

American pharmaceuticals have become perilously reliant on imports and foreign-controlled supply chains. Over the past 20 years, the country has seen a rapid increase in pharmaceutical imports and growing dependence on foreign suppliers. In 2024 alone, the United States imported over 828,000 metric tons of pharmaceutical products—a figure more than seven times higher than in 2000. Figure 1 illustrates this exponential growth.

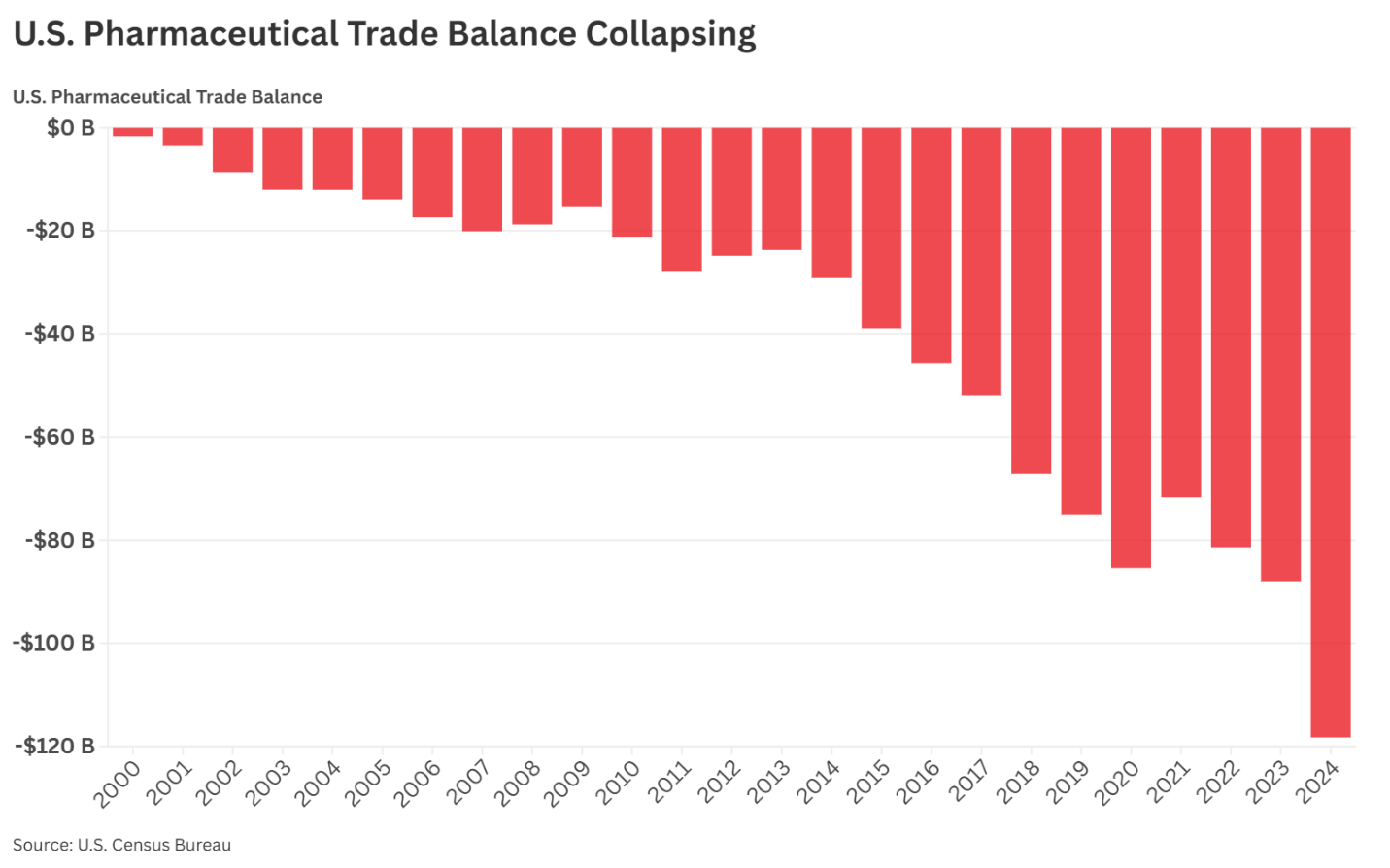

The corresponding U.S. pharmaceutical trade deficit with the rest of the world has grown from virtually zero to $118 billion over these years! (Figure 2)

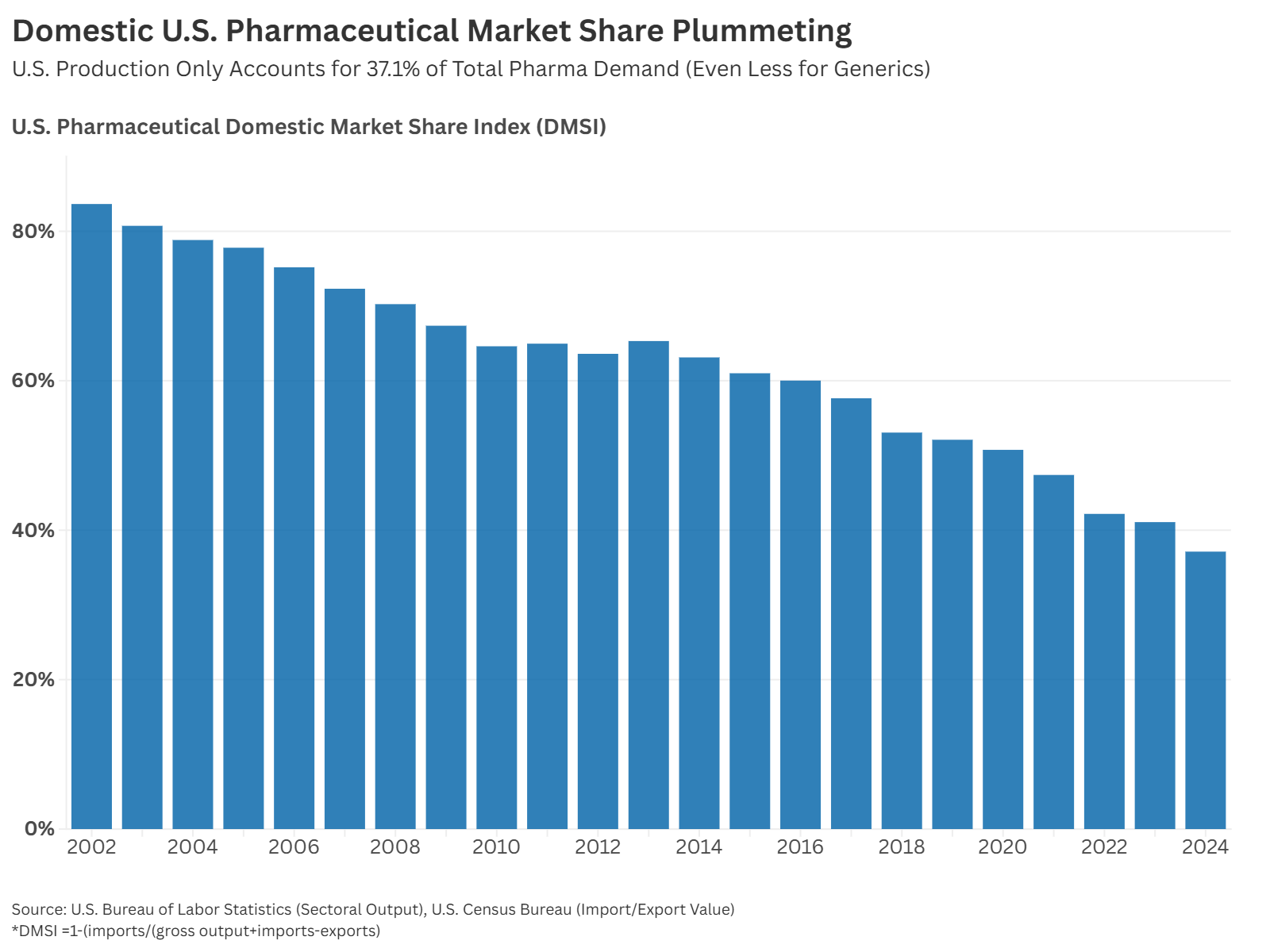

The share of American pharmaceutical manufacturers in the domestic market has more than halved over these years, from 83.7% in 2002 to just 37.1% by 2023 (Figure 3).

This staggering statistic reflects not an increase in domestic demand but a dangerous failure of globalization policy: the complete abandonment of U.S. production in favor of cheaper, riskier foreign alternatives—generic drugs. The result is not only a collapsing pharmaceutical trade balance but also the erosion of U.S. sovereignty over one of the most critical sectors of the national economy.

For example, the U.S. now has only one facility producing amoxicillin—a widely used antibiotic for treating many illnesses. In the past, this plant in Bristol, Tennessee, produced enough amoxicillin to treat the entire country. As recently as 2008, the plant covered nearly all U.S. demand for amoxicillin. But now, it is struggling to stay afloat and avoid closure, pleading for government support.

The issue is that after USAntibiotics' patent on amoxicillin expired in 2002, foreign generic manufacturers entered the market, often offering lower prices.

Paradoxically, however, the policy of "open doors" in pharmaceutical trade has exacerbated drug shortages in the U.S. Currently, the country faces shortages of 270 medications, slightly down from the record high of 323 in early 2024 https://www.ashp.org/drug.... This shortage includes many critically important everyday categories—sterile injectables, antibiotics, cancer drugs, and other medications doctors rely on daily to treat infections, relieve pain, and save lives. Surveys show that 85% of hospitals report pharmaceutical shortages as critical or moderate, forcing them to ration, delay, or even cancel treatments, putting patients at direct risk.

This shortage demonstrates that the U.S. liberal trade system has failed to ensure stable drug supplies while bankrupting domestic manufacturers that once supported them.

The free trade system promised lower drug prices domestically, but this market has proven far more complex than simplistic liberal notions of supply and demand. The nuances of importing generic drugs are so convoluted and unpredictable that hospitals report paying 300–500% markups for critical medications during periods of high demand. This means the short-term "cheapness" of imports evaporates instantly during crises—events that, in recent years amid escalating global problems, have far surpassed the popular "black swan" concept in frequency.

We will explore the factors and negative consequences of foreign pharmaceutical dominance in the U.S. in more detail in the next article.