In 2012, the Brookings Institution identified three manufacturing subsectors employing an unusually high proportion (over 30%) of engineering and scientific personnel as "very high-tech" industries:

Although these subsectors do not cover the entire high-tech manufacturing sector, they represent a significant portion of it.

American economist David Waldron analyzed data from 1990 to 2024, demonstrating a significant decline in employment specifically in these branches of the US economy. Since 1990, the number of employees in these subsectors has dropped by nearly 1 million people. In the computer and electronics industry, employment shrank by 850,000, and in aerospace by almost 300,000. Only the pharmaceutical sector and medical devices saw job growth, with a net increase of just 189,000 workers.

As a share of total employment, the decline was even sharper. Employment in high-tech manufacturing fell from 2.8% to 1.3%, a 50% reduction in its share of overall employment.

The share of this super-high-tech manufacturing in the economy also declined: from 4.8% in 1987 to just 2.6% in 2023.

While the decline of high-tech manufacturing is evident in both employment trends and output, some optimism followed the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act, allocating billions in tax credits to stimulate semiconductor production in the US. Although the CHIPS Act led to a boom in plant construction for computer and electronic products, its impact on industry employment remains difficult to see because semiconductor factories have not yet opened. Delays with workforce issues at TSMC Phoenix highlight potential staffing problems. The new President Trump’s lukewarm stance on this law and his preference for tariffs over subsidies may add further uncertainty. Despite this, estimates of the CHIPS Act’s employment impact range from only 36,300 to 56,000 jobs—covering just 4–6% of the total decline in employment over the past 35 years.

America’s share of the global market—a well-known indicator of competitiveness—is falling in one high-tech sector after another. For example, since the mid-1990s, the US share of global semiconductor production has dropped from 37% to 12%.

This problem extends beyond high-tech and affects many medium-tech industries that form the backbone of developed economies. For example, according to a recent McKinsey study, from 1995 to 2020, the US lost the following share of the global market:

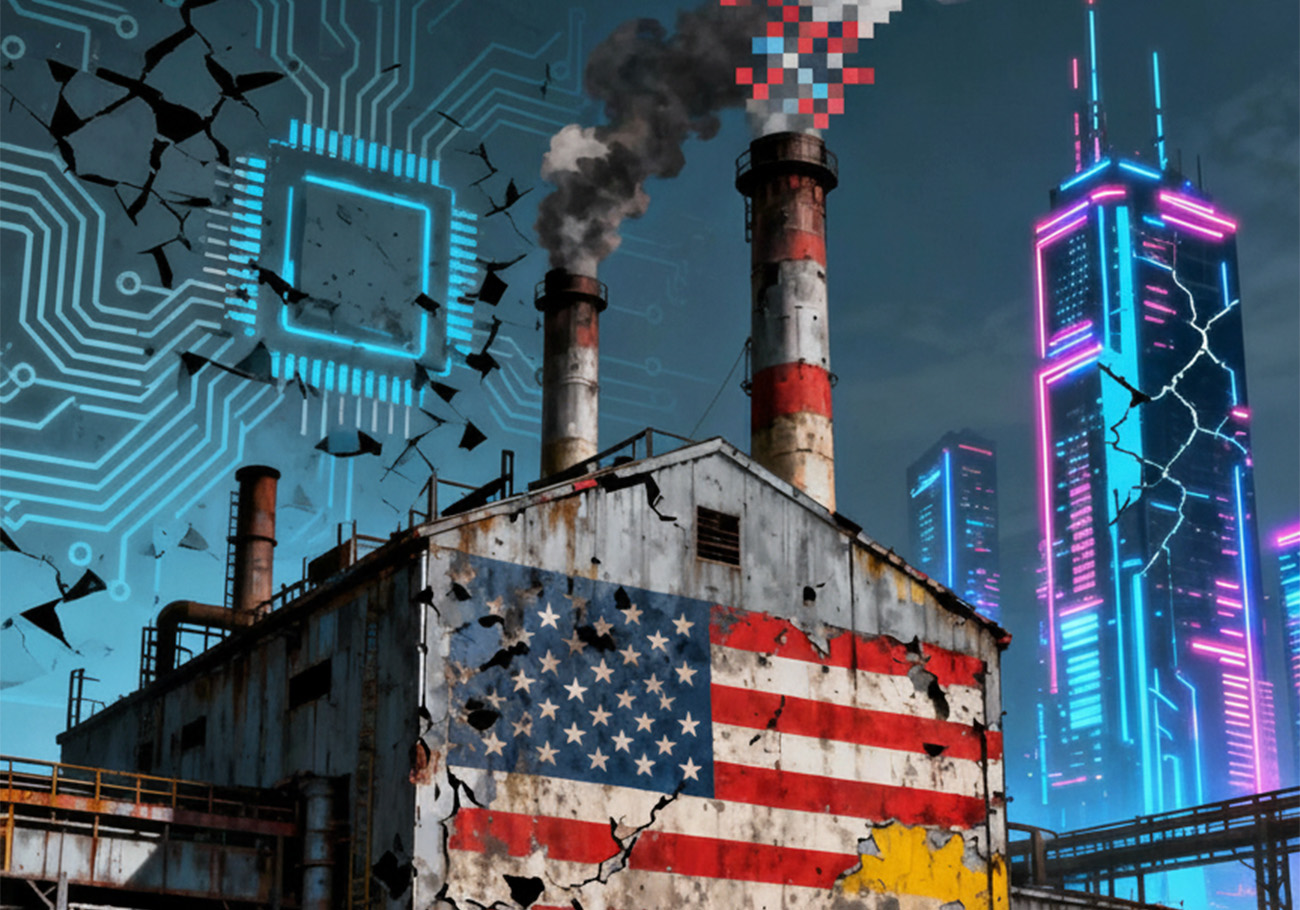

Thus, America is being displaced not only from super-high-tech, but also other sectors of manufacturing. By whom? Other countries, primarily China but also others, advancing their industries thanks to proactive industrial policies.

Why was this issue not perceived sharply for so long in economic literature and the socio-political space? It’s because, in the process of prolonged technological development, inertia in core macroeconomic indicators obscures trends in industrial competitiveness. Countries on a long-term trajectory of industrial growth first achieve competitiveness in certain industries and then prosper from it for years. Meanwhile, countries on a path of long-term industrial decline can, for a time, exhibit successful macroeconomic dynamics thanks to accumulated potential, masking deeper problems.

A classic example of this is postwar Britain. In the 1959 elections, the unofficial slogan of Britain’s Conservative Party was: “You’ve never had it so good.” That year, Britain’s economy grew by 4.1%, and the next by 6.3%—signs of huge success. But by then, the UK’s industrial base was already crumbling. Over a generation, the country’s manufacturing power, global influence, and middle class collapsed.

Today, America increasingly resembles its overseas cousin of 70 years ago. Years of neoliberal policy and neglect of industrial strategy have led to the industrial degradation described above. The desperate move toward industrial policy in Bidenomics and Trumponomics does not guarantee a fix for this tragic situation.